And, as you might guess, it will be Number 1 on this list.

Top 10 Lou Gehrig Moments

10. July 14, 1942: The Pride of the Yankees premieres. Gary Cooper was one of the top American actors of the era, and he did look a bit like Lou Gehrig. He didn't sound much like him (Gehrig had a N'Yawk accent), and had never played baseball before. It doesn't matter: It was a great story, and some of the best film of those old ballparks is in this movie.

Teresa Wright plays Lou's wife Eleanor. Babe Ruth, Bill Dickey, Bob Meusel and Mark Koenig, all real teammates of Lou's, play themselves. Walter Brennan and Dan Duryea play sportswriters. The climactic speech is close to the way it was in real life, but has the key line at the end, not near the beginning.

In 1978, A Love Affair: The Eleanor and Lou Gehrig Story premiered, starring Edward Herrmann (better known as a voiceover artist) as Lou and Blythe Danner (better known as Gwyneth Paltrow's mother) as Eleanor.

This film was willing to go where the previous one was not: It showed that Lou's mother was no saint, and it didn't make Lou Gehrig Day the end, depicting just how far the disease that would bear Lou's name had taken him.

Bob Costas would later say, "In one aspect, Lou Gehrig is ahead of Babe Ruth: The movies about Gehrig are very good, the movies about Ruth are all bad."

9. October 24, 1999: The All-Century Team. Sponsored by MasterCard, this was essentially an all-time version of the traditional All-Star Game balloting, with fans given punch-out ballots at big-league ballparks. When the votes were tabulated, Gehrig had more votes than any other player -- yes, even more than the Babe -- despite not having played a game in 60 years.

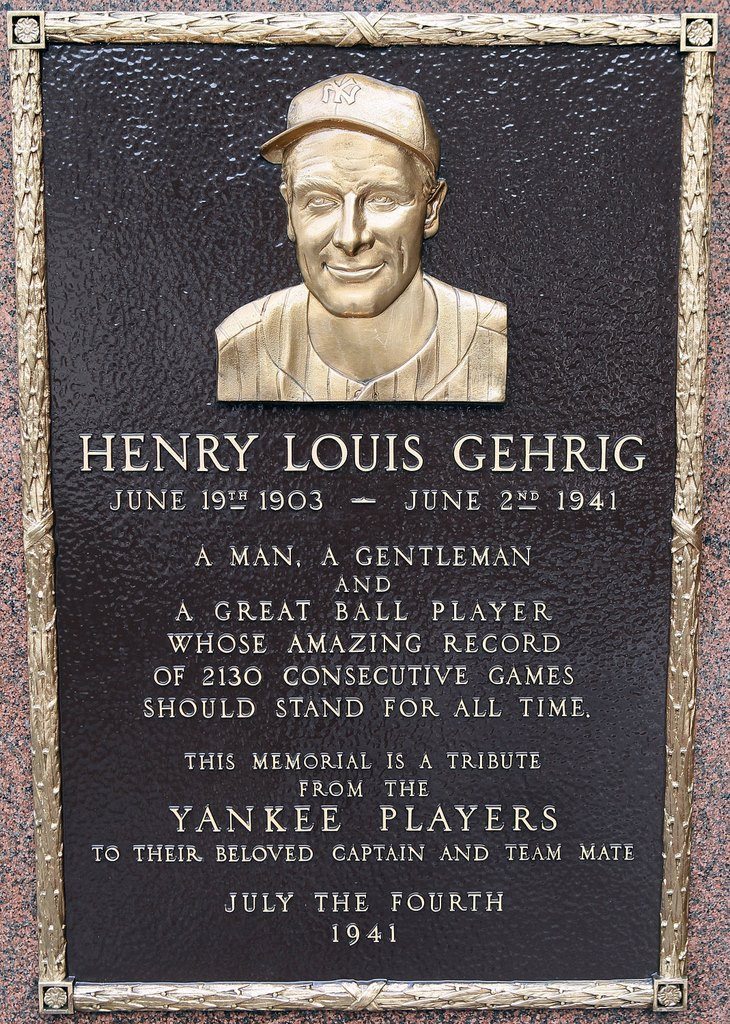

8. September 6, 1995: The Streak Revives Interest. On his Monument in Yankee Stadium's Monument Park, there are two "errors." One is the date: A rainout pushed the dedication date back from "July the Fourth 1941" to July 6. The other calls him "A man, and gentleman and a great ball player whose amazing record of 2130 consecutive games should stand for all time." That's not so much a mistake as a prediction that took an additional 54 years to be proven incorrect.

Also note that, in those days, it wasn't unusual that "ball player" was written as two words, or that there's no comma in the number.

In 1994, Phil Rizzuto was given his 3rd "day" at Yankee Stadium, and he told the fans that he never thought Ruth's records would be broken, but Roger Maris hit 61 home runs in a season in 1961 (Rizzuto had called it on WPIX-Channel 11), and Hank Aaron had hit 755 home runs, breaking the mark of 714 in 1974. "I never thought that Ripken would get close to Gehrig's record... " And since the Yankees were playing the Orioles, the fans booed.

The Scooter, knowing that this was a classless gesture, silenced the fans with, "Wait a minute! Hold the phone!" Once he had them calmed down, he told them, "Right now, Lou Gehrig is up in Heaven, hoping that Ripken breaks his record." And that got a great cheer. From then onward, Cal Ripken Jr. has never again been booed in Yankee Stadium, old or new.

When Ripken played in his 2,131st straight game, the mentions of Gehrig were plenty, and Cal was classy about it all. It should be noted that Ripken's peak batting average for a season was .340 -- and that was Lou's average for his career. Yes, Cal was one of the very best players of his era, but Lou was one of the top 10 players of all time.

In 1999, The Sporting News named its 100 Greatest Baseball Players. Cal, his career not yet complete, came in at Number 78. Lou came in at Number 6, behind Ruth, Willie Mays, Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson and Aaron.

7. October 1, 1927: His First Great Season. Until that point, no one besides Ruth had hit more than 41 home runs in a season. Lou hit 47, and had 173 runs batted in, a record. Under the rules of the time, no player could be named a League's Most Valuable Player more than once, and Ruth had already been so awarded in 1923, so Lou was named MVP.

6. April 13, 1954 and...

5. April 15, 1976: Finally, a Successor. Bill "Moose" Skowron debuted as the Yankees' starting 1st baseman on Opening Day 1954. Incredibly, the Yankees had won 10 Pennants and 9 World Championships without a great 1st baseman, until the perennial All-Star Skowron came along.

It should also be noted that, from October 8, 1939 when the Yankees won the World Series, until April 15, 1976 when Yankee Stadium reopened after its renovation, there was no official Captain of the Yankees. Men like Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, Yogi Berra and Mickey Mantle had been unofficial leaders, but there was no official Captain. The role was considered too sacred, not just because of how Gehrig had played, but also because of how he stopped.

George Steinbrenner, with his obsession with things military, thought the Yankees needed a leader, and told the press, "If Lou Gehrig had known about Thurman Munson, he would have understood." Frankly, I'm surprised that, once Thurman had also died (even younger than Lou), George didn't consider the role to be jinxed.

4. May 2, 1939. When the streak began on June 1, 1925, hardly anybody noticed. When it ended, everybody noticed. But the way he handled the end was pure class: He took himself out for the good of the team, and there was no self-aggrandizement.

By a weird twist of fate, Wally Pipp, the man he replaced as the regular Yankee 1st baseman in 1925, was in Detroit, in his new business. He went to the game. (He was 44, and, with Hank Greenberg at 1st base, there was no reason for the Tigers to offer him a contract.)

Pipp was a decent player: He led the American League in home runs in 1916 and 1917, and helped the Yankees win their 1st 3 Pennants: 1921, 1922 and 1923, including the 1923 World Series. But he lost his batting stroke in 1925, and that, and Gehrig's rise, made him expendable. He lived until 1965.

3. September 30, 1934: The Triple Crown. Lou batted .363, hit a career-high 49 home runs, and had 166 RBIs, enough to lead both Leagues in those 3 categories. This made him the 1st Yankee to win the Triple Crown. The only one to do so since is Mickey Mantle in 1956. Ruth never did it. Nor did DiMaggio, nor has anyone else.

He still didn't win the MVP, though, and it wasn't because of eligibility reasons, either: With the new version introduced by the Baseball Writers Association of America in 1931, he was eligible for as many as he could get.

But in 1934, Mickey Cochrane, as catcher and manager, led the Detroit Tigers to the Pennant, and was named MVP. I can't argue with that: I have long maintained that the most valuable player on the Pennant winner should be the MVP of the League -- although Hank Greenberg, statistically speaking, was a better candidate for the Tigers than Cochrane.

Greenberg would later nearly break Ruth's home run record (hitting 58 in 1938) and Gehrig's AL RBI record (getting 183 in 1937). Greenberg probably should have been a Yankee, but with Gehrig at 1st base, they didn't need one.

2. June 3, 1932: Four Home Runs. Lou played probably the best game ever played by a Yankee hitter, or any American League hitter. Against the Philadelphia Athletics at Shibe Park (later renamed Connie Mack Stadium), Lou went 4-for-6. Those 4 hits were all home runs, making him the first player in the AL's 32-year history to hit 4 in a game, and the only Yankee to do so. (No, Ruth, DiMaggio, Mantle, Alex Rodriguez, et al. never did it.)

He nearly had a 5th, which nobody's done in the majors (and, as far as I know, only 1 has in the minors), hitting a drive to the furthest center field corner of the park, which was hauled in. Center field at Shibe was 447 feet from home plate (later shortened to 410). He did once hit a home run past that point, and he and the A's Jimmie Foxx are the only major leaguers to do so. (I think a Negro Leaguer may also have done it; whether it was Josh Gibson or another, I don't know.)

1. July 4, 1939: Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day. This wasn't the first "day" the Yankees gave a player, nor even the first they gave to Lou (he'd previously gotten one in 1937). He didn't even want this one: He didn't want the Yankees to use his name and illness to artificially boost the crowd. So the ceremony was held between games of a 4th of July doubleheader, against the Washington Senators. (For the record, the Senators won the opener, 3-2, and the Yankees won the nightcap, 11-1.)

On one sideline, the current Yankees lined up. On the other, all the members (all then still alive) of his 1st World Series-winning team, the 1927 Yankees. (He was a member of 5 World Championship teams -- although he played in 1923 and 1939, he wasn't on the Series roster either time, so "only" 1927, '28, '32, '36 and '38 are counted.) Lou and the Babe had been feuding for a few years, and for the tail end of their status as teammates hadn't spoken off the field. Knowing that this could well be it, the Babe embraced Lou, and whatever the cause (I've heard conflicting stories), all was forgiven.

The '27 World Championship flag was raised (temporarily taking the place of the '38). George Pipgras, one of his teammates and now an AL umpire, was assigned to the games. (In the interest of fairness, today, such an ump would have been permitted to attend but not call the game.) Walter Johnson, then a Senator coach and perhaps the greatest pitcher who ever lived, was also on hand.

Lou was given all kinds of gifts, including one from the New York Giants, whom the Yankees had knocked off the perch of "greatest franchise in baseball" in the early 1920s, and (with Lou) had beaten in the 1936 and '37 Series.

The Mayor at the time, Fiorello LaGuardia (a Yankee Fan who once represented a part of The Bronx in Congress), spoke, and presented a proclamation from the City. His Number 4 was retired, the 1st uniform number retired in baseball, making him the only Yankee to ever wear it. (The team had begun wearing numbers in 1929.)

At first, Lou, very self-conscious of how he'd been slowed and weakened by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, didn't want to come forward and speak. But the fans in the crowd of 61,808 (about 5,000 short of a sellout, although there may have been complimentary tickets not counted) chanted, "We want Lou! We want Lou! We want Lou!" So he stepped to the microphone.

The newsreel cameras did not capture the entire speech. Stops and restarts can clearly be seen. Based on what's seen on film, and what was reported in newspapers that night (this was the era of evening as well as morning newspapers) and the next day, this, totally made up on the spot, is probably what he said, known due to both its eloquence and its brevity as "Baseball's Gettysburg Address":

For the past two weeks, you've been reading about a bad break.

Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth.

I have been in ballparks for 17 years, and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans.

When you look around, wouldn't you consider it a privilege to associate yourself with such fine-looking men as are standing in uniform in this ballpark today? Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn't consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day?

Sure, I'm lucky. Who wouldn't consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball's greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To have spent 6 years with that wonderful little fellow, Miller Huggins? Then to have spent the next 9 years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy? Who wouldn't feel honored to room with such a grand guy as Bill Dickey?

Sure, I'm lucky. When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift - that's something. When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies - that's something.

When you have a wonderful mother-in-law, who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own daughter, that's something. When you have a father and a mother, who work all their lives so you can have an education and build your body, it's a blessing. When you have a wife, who has been a tower of strength, and shown more courage than you dreamed existed, that's the finest I know.

So I close in saying that I may have been given a bad break, but I've got an awful lot to live for. Thank you.

It's been disputed as to how well it was known that the disease he had was fatal. Some people had no idea. But when Lou finished, the people in the stands were roaring through their tears.

A little over 2 years later, on June 2, 1941, he was dead, not quite 38 years old.

The last living player from either game in the doubleheader on Lou Gehrig Day was Buddy Lewis, who played 3rd base for the Senators in the 2nd game, and went 1-for-4. He lived until 2011. The last surviving Yankee was Tommy Henrich, who lived until 2009.

Aside from Gehrig, other victims of ALS include astrophysicist Stephen Hawking (who's lived with it for over half a century), Chinese dictator Mao Zedong; Henry Wallace, Franklin Roosevelt's 1st Secretary of Agriculture and 2nd Vice President Senator Jacob Javits of New York; General Maxwell Taylor, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the early 1960s; musicians Huddie "Leadbelly" Ledbetter, Charles Mingus, Mike Porcaro of Toto, and the still-living Jason Becker; actors David Niven, Dennis Day, Michael Zaslow and Lane Smith; comedian Ronnie Corbett; Sesame Street co-creator Jon Stone and, from the world of sports, Hall of Fame Yankee pitcher Jim "Catfish" Hunter, early 1950s Heavyweight Champion Ezzard Charles, 1960s Scottish soccer star Jimmy "Jinky" Johnstone, and English football manager Don Revie.

(UPDATE: As of July 4, 2025, 86 years after the speech, Becker is still alive, but the disease has finally killed Hawking, actor-playwright Sam Shepard, and also San Francisco 49ers receiving legend Dwight Clark. Atlanta Falcons defensive lineman turned announcer and author Tim Green also has it. With Hawking's death, Becker is the longest-lived still-living diagnosee.)

Sportswriter Mitch Albom saw his former Brandeis University sociology professor, Morris Schwartz, talk about his disease with Ted Koppel on ABC News' Nightline. Albom went back to see him, and that became the basis of his book Tuesdays With Morrie.

The disease still defies research. The treatments that have been found haven't been very effective, and a cure might take another 75 years.

But Lou Gehrig lives. As Thomas Boswell, the great baseball writer of The Washington Post, puts it, we live in a disposable society, but we don't dispose of baseball legends. We treat these men as friends, and as contemporaries though they are dead.

No comments:

Post a Comment