Say, hey, do you know of any other baseball player who's enough of a cultural icon that his name has been worked into

The Honeymooners,

Peanuts and

Star Trek?

And was on What's My Line? Twice?Nope, not even Babe Ruth, the one and only player selected ahead of Mays in The Sporting News' 1999 list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players.

Willie Howard Mays Jr. was born on May 6, 1951 in Westfield, Alabama, and grew up in nearby Fairfield, both outside Birmingham. His father, Willie Sr., nicknamed Kitty-Kat, had played semi-pro baseball, though not officially in what became known as the Negro Leagues. Willie Jr. was signed to play in those, in 1948, by the Birmingham Black Barons. He was just 17, but was good enough to help them win the Pennant, before losing the Negro World Series to the Pittsburgh-based Homestead Grays.

While playing with the Black Barons in 1949, he was pursued by several teams. He could have ended up with the Brooklyn Dodgers, on the same team with Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella. He would have played center field, and the Dodgers would have solved their left field problem by moving Duke Snider over. But the Dodgers couldn't make the deal.

He could have ended up with the Boston Red Sox, because they had offered him a tryout, because they had offered his manager in Birmingham, Piper Davis, a contract. But a Sox scout told team owner Tom Yawkey that Mays "couldn't hit a curveball." He was 18 years old, and had never yet attempted to hit a white man's curveball. And Davis was too old to keep, and was released. And that's why the Red Sox became the last major league team to integrate, in 1959. And that's also how the Red Sox could have ended up with Ted Williams in left field and Willie Mays in center field, but didn't.

The Boston Braves were also interested in Mays. But they had a quota on the number of black players in their system, and they'd already hit it. So they could have had Willie Mays in center field and Hank Aaron in right field -- perhaps not soon enough to save them from moving to Milwaukee in 1953, but the Braves could have dominated the National League for years to come.

Or, the New York Giants could have. Because their scout, Ed Montague, signed Willie, they were also interested in Hank. "I had the Giants' contract in my hand," Aaron would later say, "but the Braves offered $50 a month more. That's the only thing that kept Willie Mays and me from being teammates: Fifty dollars." $50 in 1952, with inflation, is about $552 in 2022 money. On such hinge moments does the history of a sport sometimes hang in the balance.

For 1950, the Giants assigned him to their Class A team, the Trenton Giants. This was the end of the line for minor-league baseball in New Jersey: The Giants moved both their Trenton and their Jersey City farm teams after the season, while the New York Yankees moved their Newark Bears farm team a year earlier. The Negro Leagues' Newark Eagles folded after 1951.

Negro League stars being picked up by the white majors hurt them, but what really killed the Negro Leagues and many of the minor-league teams, and in some cases entire minor leagues, was television: Why should a fan get in his car and drive 20 miles, and then pay to get in, to watch a minor-league team when he could stay home, and watch the closest major league team for free, on a TV set he'd already paid for, with food and drinks he'd already paid for and didn't have to stand on line for?

Mays did well enough with Trenton that he was promoted to the Giants' top farm team for 1951, the Class AAA Minneapolis Millers. He was batting .477, and had just turned 20. Clearly, he could hit a major league white man's curveball. So, on May 25, 1951, he made his debut with the Giants. Wearing Number 14 -- he would soon switch to 24 -- playing center field and batting 3rd, he went 0-for-5 against the Philadelphia Phillies at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. The Giants won, anyway, 8-5.

The next day, against Phils ace Robin Roberts, he went 0-for-3 with 2 walks. The Giants won, anyway, 2-0. The next day, he went 0-for-4. The Giants won, anyway, again 2-0. He had played flawlessly in center field. But at the plate, he was 0-for-12. His batting average was .000. His slugging percentage was .000. Counting the 2 walks, his on-base percentage was .143.

He told Giant manager Leo Durocher that he didn't think he was ready. Leo showed confidence him, saying, "I don't care if you go 0-for-50. I'm the manager, and you're my center fielder."

The next night, May 28, was Mays' 1st home game, at the Polo Grounds at 157th Street and 8th Avenue in Upper Manhattan, with Harlem to the south, Washington Heights to the west, and the Harlem River and The Bronx to the north and east -- including Yankee Stadium, one mile due east. The Giants were starting a series with the Boston Braves.

In the 1st inning, the Braves -- who did not yet have Aaron, or their other Hall of Fame hitter of the era, Eddie Mathews, either -- tagged Sheldon Jones for 3 runs in the top of the 1st inning. In the bottom of the 1st, batting 3rd for the 4th game in a row, was Mays. The Braves' starting pitcher was Warren Spahn, also a future Hall-of-Famer.

The distance from the pitching rubber to home plate is 60 feet 6 inches. Spahn threw him a fastball, and, after the game, told the press, "For the 1st 60 feet, that was a hell of a pitch." Mays hit it over the left field roof. It was the 1st of 3,293 career hits, the 1st of 660 home runs, and the 1st of 1,909 runs batted in. But it was the only run Spahn allowed, as the Braves won, 4-1.

Mays finished the game 1-for-4. He was now batting .063, on-base .261, slugging .250. Many years later, years in which Mays had terrorized the National League with his hitting, running and fielding, Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals jokingly told Spahn, "If you'd just struck him out, we might have been rid of him forever!"

Mays' performance in the field had led to the moving of Bobby Thomson from center field to 3rd base. When Thomson hit "The Shot Heard 'Round the World" to give the Giants the Pennant, a little more than 4 months later, Mays was on deck. He had finished a season in which he batted .274 with 20 home runs, 61 runs batted in, and some sensational catches, which led to him telling his teammates, "Say, hey, didn't you see that play?" Which led to him being nicknamed "The Say Hey Kid." He was named the NL's Rookie of the Year.

*

Willie spent most of the 1952 season, and all of the 1953 season, in the U.S. Army, drafted during the Korean War. He spent most of his service at Fort Eustis in Newport News, Virginia. He was discharged in time to rejoin the Giants during Spring Training in 1954. He won the NL batting title and its Most Valuable Player award, hitting 51 home runs.

He also won over the kids of New York, playing stickball in the streets near the Polo Grounds. He won over everybody, with his infectious enthusiasm, yelling, "Say, hey, did you see that play?" whenever he made a great play, which was often. He became known as "The Say Hey Kid."

He also got

the greatest song any baseball player has ever had, sung by The Treniers. That instrumental bridge, which includes "Take Me Out to the Ball Game," is a landmark: You can almost hear the transition from the Big Band Era of the 1930s and '40s to the epoch of Rock and Roll. Of course, these black singers had to call the 23-year-old Mays "a growing boy." And while he could hit it "farther than Campy can," they had to site a black slugger like Roy Campanella. God forbid they say he hit the ball further than a white slugger like Campy's Brooklyn Dodger teammate, Duke Snider. Even though he did.

Game 1 of the World Series was played at the Polo Grounds in New York. The game was tied 2-2 in the top of the 8th, but the Cleveland Indians got Larry Doby on 2nd base and Al Rosen on 1st with nobody out. Giant manager Leo Durocher pulled starting pitcher Sal Maglie, and brought in Don Liddle, a lefthander, to face the lefty slugger Vic Wertz, and only Wertz.

Liddle pitched, and Wertz swung, and drove the ball out to center field. The Polo Grounds was shaped more like a football stadium, so its foul poles were incredibly close: 279 feet to left field and 257 to right. In addition, the upper deck overhung the field a little, so the distances were actually even closer. But if you didn't pull the ball, it was going to stay in play. Most of the center field fence was 425 feet from home plate. A recess in center field, leading to a blockhouse that served as both teams' clubhouses -- why they were in center field, instead of under the stands, connected to the dugouts, is a mystery a long-dead architect will have to answer -- was 483 feet away.

At this moment, Mays was, in the public consciousness, where Babe Ruth was in May 1920, where Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams were in May 1941, where Mickey Mantle was in May 1956, where Reggie Jackson was in September 1977, where Roger Clemens was in April 1986, where Derek Jeter was in September 1996, where David Ortiz was in September 2004: A star, well-known and popular, but not yet a legend.

Mays ran back to try to catch the ball. In mid-stride, he thumped his fist into his mitt. His teammates, who had seen this gesture before, knew that this meant that he thought he would catch it. But most fans, who didn't watch him every day, didn't know this. Watching on television (NBC, Channel 4 in New York), they figured the ball would go over his head, scoring Doby and Rosen, and that Wertz, not exactly fleet of foot, had a chance at a triple, or even an inside-the-park home run.

Willie said many times that he was already thinking of the throw back to the infield, hoping to hold Doby to only 3rd base. With his back to the ball all the way, he caught the ball over his head, stopped, pivoted, and threw the ball back to the infield. Doby did get only to 3rd.

The announcers were Jack Brickhouse, who normally did the home games for both of Chicago's teams, the Cubs and the White Sox, but was the lead announcer for NBC in this Series; and Russ Hodges, the usual Giants announcer, made nationally famous 3 years earlier when Bobby Thomson's home run made him yell, "The Giants win the Pennant!" over and over again.

Brickhouse: "There's a long drive, way back in center field, way back, back, it is... Oh, what a catch by Mays! The runner on second, Doby, is able to tag and go to third. Willie Mays just brought this crowd to its feet with a catch which must have been an optical illusion to a lot of people. Boy! See where that 483-foot mark is in center field? The ball itself... Russ, you know this ballpark better than anyone else I know. Had to go about 460, didn't it?"

Hodges: "It certainly did, and I don't know how Willie did it, but he's been doing it all year."

It has been argued by many, including Bob Feller, the pitching legend sitting on the Indians' bench that day, that the reason so much is made of this catch is that it was in New York, it was in the World Series, and it was on television. "It was far from the best catch I've ever seen," Feller said. Mays himself would say he'd made better catches. But none more consequential.

Durocher yanked Liddle, and brought in Marv Grissom. Upon reaching the Giant dugout, Liddle told his teammates, "Well, I got my man." Yeah, Don. You got him. As Jim Bouton, then a 15-year-old Giant fan who'd recently moved from Rochelle Park, Bergen County, New Jersey to the Chicago suburb of Chicago Heights, Illinois, would later say, "Yeah, surrrre!"

Grissom walked Dale Mitchell to load the bases with only 1 out. But he struck out Dave Pope, and got Jim Hegan to fly out, to end the threat. When the Giants got back to the dugout, they told Willie what a hard catch it was. He said, "You kiddin'? I had that one all the way."

The game went to extra innings. Future Hall-of-Famer Bob Lemon went the distance for the Tribe, but in the bottom of the 10th, he walked Mays, who stole 2nd. Then he intentionally walked Hank Thompson to set up an inning-ending double play. It didn't happen: Durocher sent Dusty Rhodes up to pinch-hit for left fielder Monte Irvin, and Rhodes hit the ball down the right-field line. It just sort of squeaked into the stands.

On the film, it looks a little like a fan reached out, and it bounced off his hand. A proto-Jeffrey Maier? To this day, no one has seriously argued that the call should be overturned.

The game was over: Giants 5, Indians 2. The Indians, heavily favored to win the Series, never recovered, and the Giants swept. Willie turned out to be the last living player in both the Bobby Thomson Game and in the game where he made The Catch. He was also the last living player from the "past" segment of Terry Cashman's 1981 song "Talkin' Baseball (Willie, Mickey and the Duke)."

*

For 4 glorious years -- 1954, 1955, 1956 and 1957 -- there were 3 Hall of Fame center fielders in New York: Mays of the Giants, Snider of the Dodgers, and Mickey Mantle of the Yankees. Snider did not end up with career stats anywhere near those of Mays and Mantle, but, for a while, the comparison was legit. It ended after the 1957 season, when the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, and the Giants, including Mays, moved to San Francisco.

San Francisco is a very provincial city, preferring its own people to outsiders. Orlando Cepeda was the 1st Giant hero who began in San Francisco, Juan Marichal the 2nd, Willie McCovey the 3rd. They've always been more popular there than Mays. Frank Conniff of the New York Journal-American, perhaps the only man ever to interview both men, wrote, "This is the damnedest city. They cheer Khrushchev and boo Willie Mays."

On April 30, 1961, Mays hit 4 home runs in a game against the Milwaukee Braves. He helped the Giants win another Pennant in 1962. He should have been named NL MVP, but it went to Maury Wills of the Dodgers, after setting a new single-season record with 104 stolen bases. He did win another in 1965, hitting a career-high 52 home runs, but the Giants didn't win another Pennant until long after he retired.

The Giants lost the World Series to the Yankees. But not before Clete Boyer had the experience of hitting a ball, and, by his own admission, "My first thought was, 'Hello, double!' and then I realize, 'Oh, shit, he's out there!'" And many was the time when he hit a drive, and someone said, "The only man who could have caught it, hit it."

For a while, there was a question as to who would get to Babe Ruth's career record of 714 home runs first: Mays, or Mantle. On August 2, 1965, Mays hit his 478th homer, surpassing Mantle. On September 13, he hit his 500th. On May 4, 1966, he hit his 512th, surpassing an earlier Giant, Mel Ott, as the NL's all-time leader. On June 27, he hit his 522nd, surpassing Ted Williams for 3rd place, all-time. On August 17, he hit his 535th, surpassing Jimmie Foxx for 2nd.

But in 1968, Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves, only 34 years old, hit his 500th, and, suddenly, there was a new contender. Mays hit his 600th on September 22, 1969, but was slowing down. On July 3, 1970, he collected his 3,000th career hit. This made him the 2nd player to have 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. Aaron beat him to the distinction by a few weeks.

The Giants won the NL Western Division title in 1971, but, clearly, at 40, Mays was no longer the team's most important player -- even though he was now making more money than any player ever had, $160,000 -- about $1.24 million in 2024 money.

On May 11, 1972, the Giants traded him to the Mets, even-up, for Charlie Williams, a pitcher who lasted in the major leagues from 1971 to 1978, and had a career record of 23-22. It's not fair to say that he was a bad pitcher, but it is fair to say that being traded for Mays was the only interesting thing about his career.

Before his 1st game with the Mets, on May 14, against the Giants, Mays was presented on the field with a mockup of a San Francisco cable car. He hadn't played a home game in New York in nearly 15 years, but he was still beloved there. He led off, played 1st base, and, of course, wore Number 24. Except for a few games at the start of his career, when he wore 14, he had always worn 24. There didn't seem to be any significance to it: It was just the number he was assigned at the time.

In every city where he had a home, he applied to have the last 4 digits of his phone number be 2424. However, his California license plate didn't have the number in it: It read "SAY HEY."

Peanuts cartoonist Charles Schulz, a native of St. Paul, Minnesota who had seen Mays play for the the Minneapolis Millers, and then had moved to Northern California and become a Giants fan, once showed Charlie Brown remembering his locker combination of 3-24-7 by telling Linus Van Pelt, "Babe Ruth was Number 3, Willie Mays is Number 24, and Mickey Mantle is Number 7!"

And in that return game with the Mets, he hit a home run, the 647th of his career, and it provided the winning run, as the Mets beat the Giants, 5-4 at Shea Stadium.

As with Mantle's 500th career home run, 5 years to the day before, Mays should have retired right there. As with Mantle, the next year and a half in uniform did him no good. On June 10, Aaron hit his 649th, to surpass him for 2nd place on the all-time list. Mays, once considered the likeliest player to break Babe Ruth's career record of 714 home runs, wrapped it up after the 1973 season with 660, seeing Aaron break the record at the start of the next season.

On September 25, 1973, Willie Mays Night was held at Shea Stadium, and he told the crowd, "I look at the kids over here, the way they're playing, the way they're fighting for themselves, and it tells me one thing: 'Willie, say good by to America.'" The Mets won the Pennant, but the entire country saw his last games in the World Series, and he looked terrible.

He retired with a lifetime batting average of .302, a .384 on-base percentage, a .557 slugging percentage, a 155 OPS+; 3,283 hits including 523 doubles, 140 triples and 660 home runs, and 1,903 runs batted in. He stole 339 bases, and the only player with both more home runs and more stolen bases than Mays is Barry Bonds. He still holds the record for putouts by an outfielder, 7,095.

He appeared in 24 All-Star Games, tied with Stan Musial for 2nd-most, behind Aaron's 25. The All-Star Game's MVP award is now named for Mays. He won 12 Gold Gloves, and would have won more if the award had started before 1957.

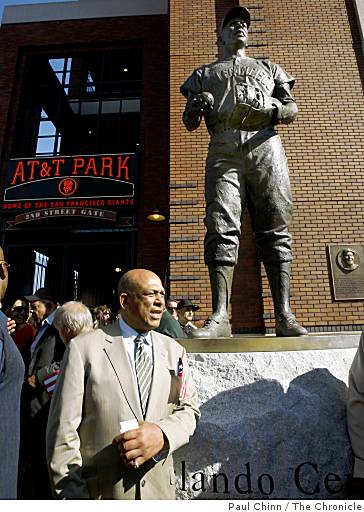

He was elected to the Hall of Fame in his 1st year of eligibility, 1979, and the Giants retired his Number 24. They gave him a statue outside their new ballpark, now named Oracle Park, whose mailing address is 24 Willie Mays Plaza.

He often wore a cap with just "G" for Giants,

instead of "NY" for New York or "SF" for San Francisco.

Original Mets owner Joan Payson, who had previously been the only stockholder of the Giants to vote against moving to San Francisco, said that no Met would ever wear Number 24 again. She died during the 1975 postseason, and, since then, 3 Mets have worn 24: Kelvin Torve for 7 games in 1990 before fans protested, Rickey Henderson (at least, another Hall-of-Famer) for 152 games in 1999 and 2000, and Robinson Canó for 168 games from 2019 to 2022. (Before Mays, the best Met to wear 24 was Art Shamsky on the 1969 "Miracle" team.)

Living in Atherton, California, on the Peninsula between San Francisco and San Jose, Mays went to many Giants functions, including their World Series appearances in 1989, 2002, 2010, 2012 and 2014; and the milestone home runs of Barry Bonds, including the 756th home run that allowed Bonds to surpass Aaron as the all-time leader -- by whatever means.

Barry was the son of Bobby Bonds, a teammate of Willie's, late in his career. Bobby named Willie Barry's godfather. When Barry got to the major leagues with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he wore Number 24 in tribute to Willie. He couldn't wear that when he signed as a free agent with the Giants, so he switched to his father's 25.

Mays did not go back to Met games very often. His appearances included their 1977 Old-Timers' Day, where he appeared in a Met uniform, along with Mantle, Snider and Joe DiMaggio in their respective uniforms; the 2008 closing of Shea Stadium; and the 2013 All-Star Game at Citi Field. The Mets retired his Number 24 on August 27, 2022, as part of their 60th Anniversary celebrations. He was too frail to attend, but some of his former Met teammates were on hand.

He married Marghuerite Wendell Chapman in 1956. They adopted a five-day-old baby named Michael in 1959, and divorced in 1963. In 1971, after dating for a few years, Mays married Mae Louise Allen, a child-welfare worker in San Francisco. She died in 2013.

In 1999, The Sporting News ranked Mays 2nd to Babe Ruth on their list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players. ESPN backed that up in their 2022 ranking of the Top 100. The argument for Mays being ahead of Ruth is not just that Mays was great defensively as well as offensively, but that did what he did in a fully-integrated major leagues, whereas Ruth never faced black players. Both arguments are flawed: Ruth did face black players in postseason "barnstorming" games, and he was a great defensive player, because he was a great pitcher. Mays never threw a pitch in a regular-season game.

Willie Mays died today, June 18, 2024, at the age of 93. Some of the reaction:

* Dave Winfield, born the day of the Bobby Thomson Game, and his 1st season in the majors, 1973, was Mays' last: "It was my pleasure and honor to have played against arguably the best @mlb @MLBPA player of all time. And to call #WillieMays my friend is incrediblyspecial #RIP “Say Hey” Kid"

* Keith Hernandez, former Mets 1st baseman, who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area: "He was a great player. The best player I ever saw."

* Derek Jeter: "One of the best to ever play the game & even a better person."

* CC Sabathia, former Yankee pitcher, who also grew up in the Bay Area: "RIP Willie Mays. You changed the game forever and inspired kids like me to chase our dream. Thank you for everything that you did on and off the field. Always in our hearts."

* Jimmy Rollins, former Philadelphia Phillies shortstop and Captain, another Bay Area native: "Willie Mays was a legend amongst legends... Baseball lived deep inside of his heart."

* Earvin "Magic" Johnson, basketball legend and owner of the arch-rival Los Angeles Dodgers: "I'm devastated to hear about the passing of the legendary Hall of Famer Willie Mays."

* Billie Jean King, tennis legend, whose brother, Randy Moffitt, pitched for the Giants and was a teammate of Mays': "The great Willie Mays has passed away. It was a privilege to know him. We were both honored by @MLB in 2010 with the Beacon Award, given to civil rights pioneers. He was a such a kind soul, who gifted my brother Randy a new glove and a television during his rookie year with the . My deepest condolences to his family. He will be missed."

* Barry Bonds: "I am beyond devastated & overcome with emotion. I have no words to describe what you mean to me- you helped shape me to be who I am today. Thank you for being my Godfather and always being there. Give my dad a hug for me. Rest in peace Willie, I love you forever."

With his death, there are 7 surviving former New York Giants: Joey Amalfitano, Ozzie Virgil, Ray Crone, Jackie Brandt, Al Worthington, Joe Margoneri and Bill White.

There are 9 surviving players from the MLB All-Century Team selected in 1999: Sandy Koufax, Pete Rose, Nolan Ryan, Johnny Bench, Mike Schmidt, Cal Ripken, Roger Clemens, Mark McGwire and Ken Griffey Jr.

And Rocky Colavito is now the last surviving player from the 1960 TV show Home Run Derby.

Ted Williams, who died in 2002 but had the opportunity to see his whole career, summed him up: "If there's a guy who was born to play baseball, it was Willie Mays."

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19982379/488327984.jpg.jpg)